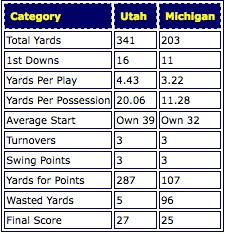

| Michigan v. Utah |

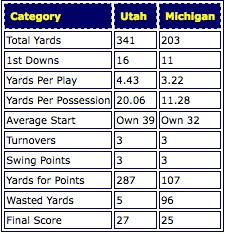

Based only on the marginal analysis, it would appear that Utah should have run away with this game. They out-gained Michigan by huge yardage overall and on a per-play basis while starting with better average field position. The Utes wasted only 5 yards of offense in the entire game (this is a huge deal: they only gained 5 total yards that didn’t contribute to a scoring effort in some way), and tied Michigan in both turnovers and swing points. So, based on this analysis, it appears as though Utah should have run away with this game. The big difference in this contest, and what allowed Michigan to keep it close, was the manner in which Utah was scoring. While the Wolverines scored 3 touchdowns and a field goal, the Utes were settling for 3-pointers for much of the day, and Louie Sakoda nailed 4 of them. Near-swing points also played a role. While none of Michigan’s touchdowns came on drives of fewer than 25 yards (as per DocSat criteria), they had a 26-yarder, a 33-yarder, and a 31-yarder. Considering Michigan’s worse average starting field position, the remainder of their drives must have started in horrible situations (and they did: 8 of Michigan’s other drives started at or inside their own 20). It seems that, unless Michigan could get good field position, the offense was destined to fail. If only we had realized it would be like that all season… Based only on the marginal analysis, it would appear that Utah should have run away with this game. They out-gained Michigan by huge yardage overall and on a per-play basis while starting with better average field position. The Utes wasted only 5 yards of offense in the entire game (this is a huge deal: they only gained 5 total yards that didn’t contribute to a scoring effort in some way), and tied Michigan in both turnovers and swing points. So, based on this analysis, it appears as though Utah should have run away with this game. The big difference in this contest, and what allowed Michigan to keep it close, was the manner in which Utah was scoring. While the Wolverines scored 3 touchdowns and a field goal, the Utes were settling for 3-pointers for much of the day, and Louie Sakoda nailed 4 of them. Near-swing points also played a role. While none of Michigan’s touchdowns came on drives of fewer than 25 yards (as per DocSat criteria), they had a 26-yarder, a 33-yarder, and a 31-yarder. Considering Michigan’s worse average starting field position, the remainder of their drives must have started in horrible situations (and they did: 8 of Michigan’s other drives started at or inside their own 20). It seems that, unless Michigan could get good field position, the offense was destined to fail. If only we had realized it would be like that all season… |

| Michigan v. Miami |

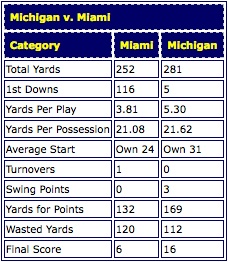

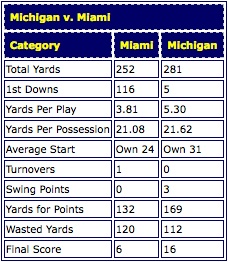

Michigan is used to dominating MAC teams. Until later in 2008, the Wolverines had never lost to a squad from the Mid-American conference. So, when Michigan won this game, it was no surprise. In terms of marginal analysis, Miami was a fairly straightforward game as well. The final 10-point margin didn’t scream “There should be a difference of more than 30 total yards between these teams.” Michigan greatly outgained the RedHawks in yards-per-play (5.30 to 3.81) and got the benefit of a single turnover by Miami to their none, and 3 swing points resulting from it.Yeah, there’s a typo in the graph. It should be 16 to 15 first downs, in favor of Miami. Michigan is used to dominating MAC teams. Until later in 2008, the Wolverines had never lost to a squad from the Mid-American conference. So, when Michigan won this game, it was no surprise. In terms of marginal analysis, Miami was a fairly straightforward game as well. The final 10-point margin didn’t scream “There should be a difference of more than 30 total yards between these teams.” Michigan greatly outgained the RedHawks in yards-per-play (5.30 to 3.81) and got the benefit of a single turnover by Miami to their none, and 3 swing points resulting from it.Yeah, there’s a typo in the graph. It should be 16 to 15 first downs, in favor of Miami. |

| Michigan v. Notre Dame |

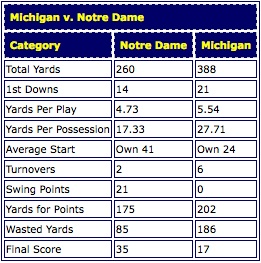

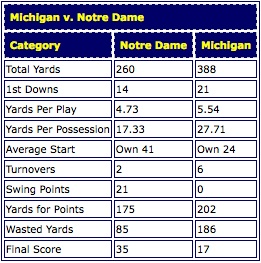

I think Doctor Saturday was peering into the future and seeing this game when he hatched the whole “Life on the Margins” concept. Looking at the boxscore, the Wolverines should have dominated the scoreboard. Michigan outgained the Irish by 128 yards overall, nearly a full yard per play, more than 10 yards per possession, and 7 overall first downs. If only that was a guaranteed way to put points on the board (awkward scoring systems in spring games notwithstanding). Michigan turned the ball over 6 times to Notre Dame’s 2, and the Irish had 21 swing points, while Michigan had 0. The Irish were very lucky to win this game (and even that against a historically-bad Michigan team), and perhaps a closer analysis would have tempered the expectations of Notre Dame fans. Without the huge disparity in turnovers and the resulting swing points, Michigan would be a hypothetical 17-14 winner of this game. Alas, turnovers are part of football, and the scoreboard ended with a big win for Notre Dame. What doesn’t make sense, however, is claiming that the Irish beat down Michigan in a reverse of the 2006 game. In fact, if you look at, like, the stat sheet, that’s a ridiculous comparison to make. Michigan dominated play in both years (340-245 in total yardage in ’06, 5.40-3.71 per play), and just so happened to get ridiculously unlucky/sloppy in ’08. Michigan fans actually came out of this game as encouraged as they could possibly be by a 3-score loss to one of their most hated rivals. Alas, aside from Michigan falling off a cliff not too long after this game, it appears as though Notre Dame’s defense was indeed just that bad, and the Irish offense was nothing special. I think Doctor Saturday was peering into the future and seeing this game when he hatched the whole “Life on the Margins” concept. Looking at the boxscore, the Wolverines should have dominated the scoreboard. Michigan outgained the Irish by 128 yards overall, nearly a full yard per play, more than 10 yards per possession, and 7 overall first downs. If only that was a guaranteed way to put points on the board (awkward scoring systems in spring games notwithstanding). Michigan turned the ball over 6 times to Notre Dame’s 2, and the Irish had 21 swing points, while Michigan had 0. The Irish were very lucky to win this game (and even that against a historically-bad Michigan team), and perhaps a closer analysis would have tempered the expectations of Notre Dame fans. Without the huge disparity in turnovers and the resulting swing points, Michigan would be a hypothetical 17-14 winner of this game. Alas, turnovers are part of football, and the scoreboard ended with a big win for Notre Dame. What doesn’t make sense, however, is claiming that the Irish beat down Michigan in a reverse of the 2006 game. In fact, if you look at, like, the stat sheet, that’s a ridiculous comparison to make. Michigan dominated play in both years (340-245 in total yardage in ’06, 5.40-3.71 per play), and just so happened to get ridiculously unlucky/sloppy in ’08. Michigan fans actually came out of this game as encouraged as they could possibly be by a 3-score loss to one of their most hated rivals. Alas, aside from Michigan falling off a cliff not too long after this game, it appears as though Notre Dame’s defense was indeed just that bad, and the Irish offense was nothing special. |

| Michigan v. Wisconsin |

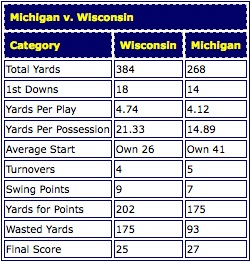

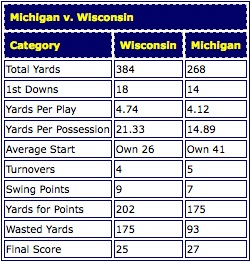

Wisconsin started the season as a top-10 team, and were still in the upper echelon of college football heading into this game. They brought an undefeated record into Ann Arbor expecting to emerge with a fourth victory. In the end, though, the Badgers would be dealt the first of their many losses on the season. The margins were kind to Michigan in the this game. The Wolverines were outgained by 116 yards (0.62 per play) and 4 first downs, committed more turnovers than their opponent, and even scored fewer swing points than the Badgers. However, they managed to come away with the win. How? The answer lies in points per score. The Badgers, like Utah before them, were forced to settle for field goals, while the Wolverines scored only touchdowns. In fact, the Badgers had 3 swing scores, but only gained 9 points on all of them combined. Michigan, on the other hand, had only 1 swing score, but John Thompson, of all people, made it count by taking the interception all the way back. Wisconsin had 4 field goal attempts (one was missed) and Michigan didn’t attempt a single 3-pointer. Making each score count was huge for Michigan. Wasted yards were also a big factor in this game, as Wisconsin wasted nearly as many yards as they used on scoring drives, while Michigan wasted about one third of theirs. Wisconsin started the season as a top-10 team, and were still in the upper echelon of college football heading into this game. They brought an undefeated record into Ann Arbor expecting to emerge with a fourth victory. In the end, though, the Badgers would be dealt the first of their many losses on the season. The margins were kind to Michigan in the this game. The Wolverines were outgained by 116 yards (0.62 per play) and 4 first downs, committed more turnovers than their opponent, and even scored fewer swing points than the Badgers. However, they managed to come away with the win. How? The answer lies in points per score. The Badgers, like Utah before them, were forced to settle for field goals, while the Wolverines scored only touchdowns. In fact, the Badgers had 3 swing scores, but only gained 9 points on all of them combined. Michigan, on the other hand, had only 1 swing score, but John Thompson, of all people, made it count by taking the interception all the way back. Wisconsin had 4 field goal attempts (one was missed) and Michigan didn’t attempt a single 3-pointer. Making each score count was huge for Michigan. Wasted yards were also a big factor in this game, as Wisconsin wasted nearly as many yards as they used on scoring drives, while Michigan wasted about one third of theirs. |

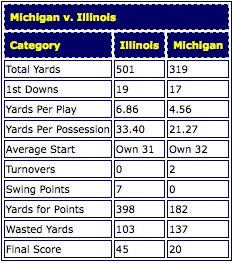

| Michigan v. Illinois |

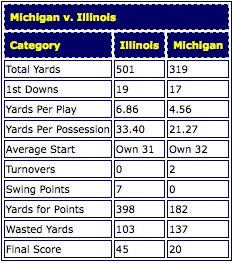

The Illinois game was really the beginning of the end for Michigan’s season. The slide, momentarily halted by an exciting win over Wisconsin, resumed in full force at home against the Illini. The defense, expected to keep Michigan in games in 2008 until the offense came around, began a slide of its own, which would continue for the remainder of the year. Juice Williams set a Big House record with 431 yards accounted for on his own. Michigan turned the ball over twice, one of which turned into 7 Illinois points. However, Michigan did, at one point, look like a competent team in this game. The Wolverines led 17-14 at halftime after their lack of depth did them in later in the game (get used to this; it’s something of a theme in Michigan’s 2008 season). Illinois dominated the second half, outscoring Michigan 31-3. A rudimentary analysis of the margins bears that out. The Illini outgained Michigan by more than 2 yards per play, wasted 20% of their yards while Michigan wasted 43%, had more swing points, total yards, first downs, etc. Led by Juice Williams, the illini were simply the better team on this day. Of course, the Illini, like the Wolverines, would unravel later in the year. The win in Ann Arbor was almost certainly Illinois’s best performance of the year. The fact that it came against the anemic offense of Michigan is understandable. The Illinois game was really the beginning of the end for Michigan’s season. The slide, momentarily halted by an exciting win over Wisconsin, resumed in full force at home against the Illini. The defense, expected to keep Michigan in games in 2008 until the offense came around, began a slide of its own, which would continue for the remainder of the year. Juice Williams set a Big House record with 431 yards accounted for on his own. Michigan turned the ball over twice, one of which turned into 7 Illinois points. However, Michigan did, at one point, look like a competent team in this game. The Wolverines led 17-14 at halftime after their lack of depth did them in later in the game (get used to this; it’s something of a theme in Michigan’s 2008 season). Illinois dominated the second half, outscoring Michigan 31-3. A rudimentary analysis of the margins bears that out. The Illini outgained Michigan by more than 2 yards per play, wasted 20% of their yards while Michigan wasted 43%, had more swing points, total yards, first downs, etc. Led by Juice Williams, the illini were simply the better team on this day. Of course, the Illini, like the Wolverines, would unravel later in the year. The win in Ann Arbor was almost certainly Illinois’s best performance of the year. The fact that it came against the anemic offense of Michigan is understandable. |

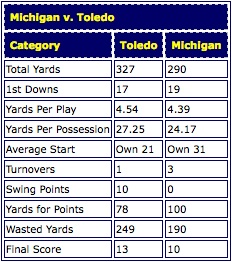

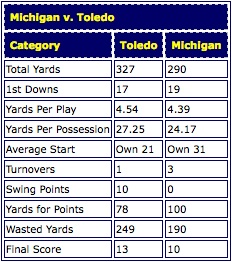

| Michigan v. Toledo |

Toledo, or as Michigan fans know it “ARGJGRFGRGFGHGH.” Michigan, despite being the more talented team, managed to lose to a MAC team, and a bad one at that. How did it happen? Surely there was a ridiculous difference in the margins, no? Surprisingly, that isn’t so much the case. The Rockets outgained Michigan 327-290 (4.54-4.39 per play), and had a deficit of only 2 first downs. Michigan, in fact, seemed to get its lunch handed to it. HOWEVA, the Wolverines were actually able to hold the Rockets when they needed to: only 78 of Toledo’s yards contributed to a score of any type. The Rockets wasted the vast majority of their yardage. Michigan used a little more than a third of theirs for scores. So how did the Rockets win? Michigan’s season-long bugaboo, the turnover, resulted in this Toledo victory. The rockets had 10 swing points, including an interception return of 100 yards by Tyrell Herbert. Michigan had no swing points, and only benefitted from one Rockets turnover. If not for a missed field goal by KC Lopata at the end of the game, the Wolverines still would have had a chance to take this one in overtime. The yards-per-play, not among the worst of Michigan’s season, contributed to one of the lowest scoring outputs based on timing. Michigan turned the ball over at the worst possible instants. On Herbert’s interception return, the Wovlerines had driven the field and were going in for the score. Had that turnover not taken place, Michigan would have likely won this game – not even accounting for the momentum swing it created. Toledo, or as Michigan fans know it “ARGJGRFGRGFGHGH.” Michigan, despite being the more talented team, managed to lose to a MAC team, and a bad one at that. How did it happen? Surely there was a ridiculous difference in the margins, no? Surprisingly, that isn’t so much the case. The Rockets outgained Michigan 327-290 (4.54-4.39 per play), and had a deficit of only 2 first downs. Michigan, in fact, seemed to get its lunch handed to it. HOWEVA, the Wolverines were actually able to hold the Rockets when they needed to: only 78 of Toledo’s yards contributed to a score of any type. The Rockets wasted the vast majority of their yardage. Michigan used a little more than a third of theirs for scores. So how did the Rockets win? Michigan’s season-long bugaboo, the turnover, resulted in this Toledo victory. The rockets had 10 swing points, including an interception return of 100 yards by Tyrell Herbert. Michigan had no swing points, and only benefitted from one Rockets turnover. If not for a missed field goal by KC Lopata at the end of the game, the Wolverines still would have had a chance to take this one in overtime. The yards-per-play, not among the worst of Michigan’s season, contributed to one of the lowest scoring outputs based on timing. Michigan turned the ball over at the worst possible instants. On Herbert’s interception return, the Wovlerines had driven the field and were going in for the score. Had that turnover not taken place, Michigan would have likely won this game – not even accounting for the momentum swing it created. |

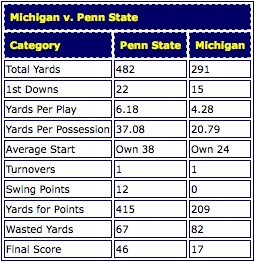

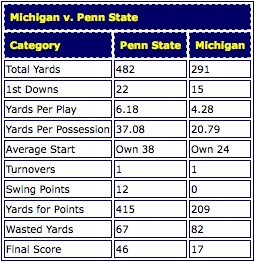

| Michigan v. Penn State |

On a macro, game-long level, Penn State dominated Michigan. The Wolverines had fewer yards (total and per-play), fewer first downs, worse starting field position, and 29 fewer points. However, it is important to point out Michigan’s success in the first half, after which they led 17-14 (including a Penn State drive with only 2 minutes left in the half to bring the margin back within a field goal). At the beginning of the second half, the tides turned. Steve Threet got hurt, Nick Sheridan took a safety, and it was all downhill from there. The momentum-killing 2-pointer led to a second-half shellacking at the hands of the Nittany Lions, and they followed it with 30 more points, including 10 more swing points. A greater man than I would look at the marginal analysis of each half of this game, to see the radical tale-of-two-halves. Without looking at the actual data, I would assume Michigan fairly dominated the first two quarters straight up, while Penn State controlled the third and fourth. Aided by the swing points they they scored, the second half was an ugly, ugly thing to behold for Michigan fans. Like the Illinois game, it was partially a testament to the lack of depth across the board on Michigan’s roster. Once the depth is built up, games aren’t likely to continue this familiar path. On a macro, game-long level, Penn State dominated Michigan. The Wolverines had fewer yards (total and per-play), fewer first downs, worse starting field position, and 29 fewer points. However, it is important to point out Michigan’s success in the first half, after which they led 17-14 (including a Penn State drive with only 2 minutes left in the half to bring the margin back within a field goal). At the beginning of the second half, the tides turned. Steve Threet got hurt, Nick Sheridan took a safety, and it was all downhill from there. The momentum-killing 2-pointer led to a second-half shellacking at the hands of the Nittany Lions, and they followed it with 30 more points, including 10 more swing points. A greater man than I would look at the marginal analysis of each half of this game, to see the radical tale-of-two-halves. Without looking at the actual data, I would assume Michigan fairly dominated the first two quarters straight up, while Penn State controlled the third and fourth. Aided by the swing points they they scored, the second half was an ugly, ugly thing to behold for Michigan fans. Like the Illinois game, it was partially a testament to the lack of depth across the board on Michigan’s roster. Once the depth is built up, games aren’t likely to continue this familiar path. |

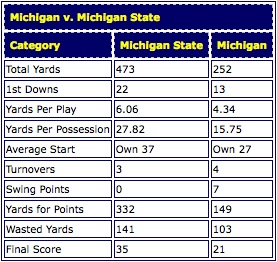

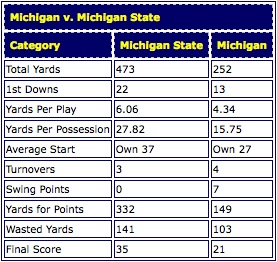

| Michigan v. Michigan State |

Sometimes, little brother wins. This was one of those instances. Sparty had more rushing yards, more passing yards, more first downs, and a significant advantage in yards-per-play. Michigan turned it over once more than did Brian Hoyer, and even though they had the game’s only swing points (on a terrible call that gave Brandon Minor a TD reception), they really had their asses handed to them. Still notable, however, is that this game was tied after three quarters. Again, Michigan’s lack of depth did them in late in the game. Looking to the future, the Wolverines really weren’t as close to Michigan State this year as they’d like to think (of course, how close can you expect a 3-9 team to be to a 9-4 team?). With Sparty losing their QB and RB, however, the Wolverines can make up ground next year. Sometimes, little brother wins. This was one of those instances. Sparty had more rushing yards, more passing yards, more first downs, and a significant advantage in yards-per-play. Michigan turned it over once more than did Brian Hoyer, and even though they had the game’s only swing points (on a terrible call that gave Brandon Minor a TD reception), they really had their asses handed to them. Still notable, however, is that this game was tied after three quarters. Again, Michigan’s lack of depth did them in late in the game. Looking to the future, the Wolverines really weren’t as close to Michigan State this year as they’d like to think (of course, how close can you expect a 3-9 team to be to a 9-4 team?). With Sparty losing their QB and RB, however, the Wolverines can make up ground next year. |

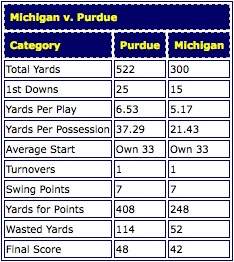

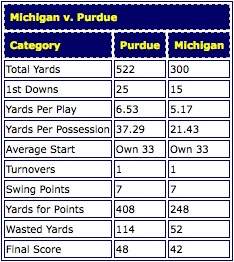

| Michigan v. Purdue |

Purdue had 522 yards of total offense. Of course, that does include a 61-yard fake punt and a 32-yard hook-and-ladder, but is 429 yards against one of the league’s sputtering offenses really that much of an improvement? The points scored on those two drive aren’t technically “swing points” but they are certainly unconventional ways in which Purdue ended up scoring, and in effect do the same thing. Without those two scores, Michigan would have won. Of course, the Boilermakers still would have outgained Michigan by 129 yards and 0.4 yards per play. The margins were fairly even in this game, as each team had 7 swing points (Michigan’s on a punt return for touchdown, Purdue’s on a fumble recovery that gave them the ball just 14 yards from paydirt), a single turnover, and identical starting field position. So yeah, that 3-3-5 experiment really sucked. Thanks, Tony Gibson. The Wolverines, afraid of the rushing threat by redshirt freshman quarterback Justin Siller, went with a run-oriented defense. In stopping the run (Purdue still ran for 256 yards, 77 of them by Siller), the Wolverines gave up the short passing game. Siller threw for 266 and 3 touchdowns, with no turnovers. The Boilermakers wasted 22% of their yards, while Michigan didn’t use 17%. Again, the timing of big plays by either team tell more of the story than the yardage itself. Purdue had 522 yards of total offense. Of course, that does include a 61-yard fake punt and a 32-yard hook-and-ladder, but is 429 yards against one of the league’s sputtering offenses really that much of an improvement? The points scored on those two drive aren’t technically “swing points” but they are certainly unconventional ways in which Purdue ended up scoring, and in effect do the same thing. Without those two scores, Michigan would have won. Of course, the Boilermakers still would have outgained Michigan by 129 yards and 0.4 yards per play. The margins were fairly even in this game, as each team had 7 swing points (Michigan’s on a punt return for touchdown, Purdue’s on a fumble recovery that gave them the ball just 14 yards from paydirt), a single turnover, and identical starting field position. So yeah, that 3-3-5 experiment really sucked. Thanks, Tony Gibson. The Wolverines, afraid of the rushing threat by redshirt freshman quarterback Justin Siller, went with a run-oriented defense. In stopping the run (Purdue still ran for 256 yards, 77 of them by Siller), the Wolverines gave up the short passing game. Siller threw for 266 and 3 touchdowns, with no turnovers. The Boilermakers wasted 22% of their yards, while Michigan didn’t use 17%. Again, the timing of big plays by either team tell more of the story than the yardage itself. |

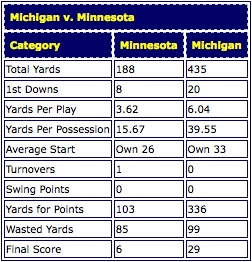

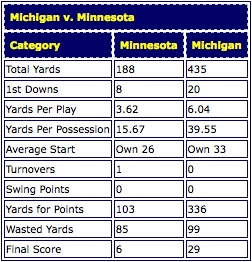

| Michigan v. Minnesota |

After being shredded by Purdue, clearly Michigan stood no chance against the potent(ish) offense and ball-hungry defense of Minnesota. Uh, not so much. The Wolverines turned the ball over once (matched by the Gophers) and gave up by far its fewest yards of the season. Michigan almost doubled up the Gophers in yard-per-play (and more than doubled their number of first downs), Nick Sheridan was competent, and Wolverines fans perhaps got a glimpse of what the future could look like under Rich Rodriguez. The gophers wasted nearly half of their yards, and Michigan wasted less than a quarter of their own. In every single way, the margins bear out that this was a dominating performance by Michigan. The Wolverines outdid the gophers in every marginal category except swing points and turnovers, in which the two teams were even. After being shredded by Purdue, clearly Michigan stood no chance against the potent(ish) offense and ball-hungry defense of Minnesota. Uh, not so much. The Wolverines turned the ball over once (matched by the Gophers) and gave up by far its fewest yards of the season. Michigan almost doubled up the Gophers in yard-per-play (and more than doubled their number of first downs), Nick Sheridan was competent, and Wolverines fans perhaps got a glimpse of what the future could look like under Rich Rodriguez. The gophers wasted nearly half of their yards, and Michigan wasted less than a quarter of their own. In every single way, the margins bear out that this was a dominating performance by Michigan. The Wolverines outdid the gophers in every marginal category except swing points and turnovers, in which the two teams were even. |

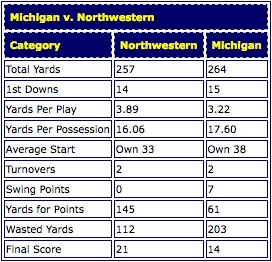

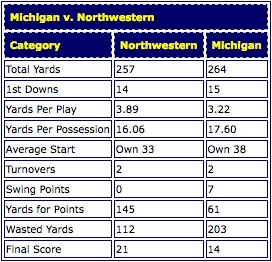

| Michigan v. Northwestern |

rMichigan outgained Northwestern by 7 yards, but they also ended up 7 short of the Wildcats in a much more important measure – points. The Wolverines scored the game’s only swing points (on a blocked punt returned to the endzone by walkon Ricky Reyes). So with advantages in perhaps the two most important categories, on top of field position, how did Michigan lose to Northwestern? The answer lies instead in wasted yards. Michigan had great field position on their first drive (Northwestern’s 8), but Nick Sheridan tossed two incompletions and KC “Kicking Consistency” Lopata missed a field goal. The offense came away empty-handed, perhaps setting the tone for the whole game. The timing of turnovers is an important factor, that isn’t readily apparent just from looking at the boxscore or the marginal analysis. Michigan’s first turnover was a killer in terms of timing. Though the 39-yard drive that ensued from that turnover doesn’t count as “swing points” in the strict terms of being shorter than 25 yards, it wasn’t far off. The missed opportunity for Michigan combined with the opportunity given directly to Northwestern. certainly hurt Michigan on the final scoreboard. This was a game that Michigan could have won, based on marginal analysis. rMichigan outgained Northwestern by 7 yards, but they also ended up 7 short of the Wildcats in a much more important measure – points. The Wolverines scored the game’s only swing points (on a blocked punt returned to the endzone by walkon Ricky Reyes). So with advantages in perhaps the two most important categories, on top of field position, how did Michigan lose to Northwestern? The answer lies instead in wasted yards. Michigan had great field position on their first drive (Northwestern’s 8), but Nick Sheridan tossed two incompletions and KC “Kicking Consistency” Lopata missed a field goal. The offense came away empty-handed, perhaps setting the tone for the whole game. The timing of turnovers is an important factor, that isn’t readily apparent just from looking at the boxscore or the marginal analysis. Michigan’s first turnover was a killer in terms of timing. Though the 39-yard drive that ensued from that turnover doesn’t count as “swing points” in the strict terms of being shorter than 25 yards, it wasn’t far off. The missed opportunity for Michigan combined with the opportunity given directly to Northwestern. certainly hurt Michigan on the final scoreboard. This was a game that Michigan could have won, based on marginal analysis. |

| Michigan v. Ohio State |

Again Michigan was within striking distance at halftime, and again their opponent used far-superior depth to slam the door on the Wolverines. This game, still, was closer than it seemed. Michigan missed a field goal, and turned it over twice to Ohio State’s once (14 swing points for OSU, 0 for Michigan). Sure, playing hypotheticals accomplishes almost nothing, but even without the changes in momentum that those events produced, that still would have meant only a 28-10 loss for Michigan, far from a blowout. But as we learned in the Notre Dame game, turnover and swing points do indeed count on the final scoreboard, and Michigan was demoralized by the Buckeyes for the second year in a row. Again Michigan was within striking distance at halftime, and again their opponent used far-superior depth to slam the door on the Wolverines. This game, still, was closer than it seemed. Michigan missed a field goal, and turned it over twice to Ohio State’s once (14 swing points for OSU, 0 for Michigan). Sure, playing hypotheticals accomplishes almost nothing, but even without the changes in momentum that those events produced, that still would have meant only a 28-10 loss for Michigan, far from a blowout. But as we learned in the Notre Dame game, turnover and swing points do indeed count on the final scoreboard, and Michigan was demoralized by the Buckeyes for the second year in a row. |

Based only on the marginal analysis, it would appear that Utah should have run away with this game. They out-gained Michigan by huge yardage overall and on a per-play basis while starting with better average field position. The Utes wasted only 5 yards of offense in the entire game (this is a huge deal: they only gained 5 total yards that didn’t contribute to a scoring effort in some way), and tied Michigan in both turnovers and swing points. So, based on this analysis, it appears as though Utah should have run away with this game. The big difference in this contest, and what allowed Michigan to keep it close, was the manner in which Utah was scoring. While the Wolverines scored 3 touchdowns and a field goal, the Utes were settling for 3-pointers for much of the day, and Louie Sakoda nailed 4 of them. Near-swing points also played a role. While none of Michigan’s touchdowns came on drives of fewer than 25 yards (as per DocSat criteria), they had a 26-yarder, a 33-yarder, and a 31-yarder. Considering Michigan’s worse average starting field position, the remainder of their drives must have started in horrible situations (and they did: 8 of Michigan’s other drives started at or inside their own 20). It seems that, unless Michigan could get good field position, the offense was destined to fail. If only we had realized it would be like that all season…

Based only on the marginal analysis, it would appear that Utah should have run away with this game. They out-gained Michigan by huge yardage overall and on a per-play basis while starting with better average field position. The Utes wasted only 5 yards of offense in the entire game (this is a huge deal: they only gained 5 total yards that didn’t contribute to a scoring effort in some way), and tied Michigan in both turnovers and swing points. So, based on this analysis, it appears as though Utah should have run away with this game. The big difference in this contest, and what allowed Michigan to keep it close, was the manner in which Utah was scoring. While the Wolverines scored 3 touchdowns and a field goal, the Utes were settling for 3-pointers for much of the day, and Louie Sakoda nailed 4 of them. Near-swing points also played a role. While none of Michigan’s touchdowns came on drives of fewer than 25 yards (as per DocSat criteria), they had a 26-yarder, a 33-yarder, and a 31-yarder. Considering Michigan’s worse average starting field position, the remainder of their drives must have started in horrible situations (and they did: 8 of Michigan’s other drives started at or inside their own 20). It seems that, unless Michigan could get good field position, the offense was destined to fail. If only we had realized it would be like that all season… Michigan is used to dominating MAC teams. Until later in 2008, the Wolverines had never lost to a squad from the Mid-American conference. So, when Michigan won this game, it was no surprise. In terms of marginal analysis, Miami was a fairly straightforward game as well. The final 10-point margin didn’t scream “There should be a difference of more than 30 total yards between these teams.” Michigan greatly outgained the RedHawks in yards-per-play (5.30 to 3.81) and got the benefit of a single turnover by Miami to their none, and 3 swing points resulting from it.Yeah, there’s a typo in the graph. It should be 16 to 15 first downs, in favor of Miami.

Michigan is used to dominating MAC teams. Until later in 2008, the Wolverines had never lost to a squad from the Mid-American conference. So, when Michigan won this game, it was no surprise. In terms of marginal analysis, Miami was a fairly straightforward game as well. The final 10-point margin didn’t scream “There should be a difference of more than 30 total yards between these teams.” Michigan greatly outgained the RedHawks in yards-per-play (5.30 to 3.81) and got the benefit of a single turnover by Miami to their none, and 3 swing points resulting from it.Yeah, there’s a typo in the graph. It should be 16 to 15 first downs, in favor of Miami. I think Doctor Saturday was peering into the future and seeing this game when he hatched the whole “Life on the Margins” concept. Looking at the boxscore, the Wolverines should have dominated the scoreboard. Michigan outgained the Irish by 128 yards overall, nearly a full yard per play, more than 10 yards per possession, and 7 overall first downs. If only that was a guaranteed way to put points on the board (awkward scoring systems in spring games notwithstanding). Michigan turned the ball over 6 times to Notre Dame’s 2, and the Irish had 21 swing points, while Michigan had 0. The Irish were very lucky to win this game (and even that against a historically-bad Michigan team), and perhaps a closer analysis would have tempered the expectations of Notre Dame fans. Without the huge disparity in turnovers and the resulting swing points, Michigan would be a hypothetical 17-14 winner of this game. Alas, turnovers are part of football, and the scoreboard ended with a big win for Notre Dame. What doesn’t make sense, however, is claiming that the Irish beat down Michigan

I think Doctor Saturday was peering into the future and seeing this game when he hatched the whole “Life on the Margins” concept. Looking at the boxscore, the Wolverines should have dominated the scoreboard. Michigan outgained the Irish by 128 yards overall, nearly a full yard per play, more than 10 yards per possession, and 7 overall first downs. If only that was a guaranteed way to put points on the board (awkward scoring systems in spring games notwithstanding). Michigan turned the ball over 6 times to Notre Dame’s 2, and the Irish had 21 swing points, while Michigan had 0. The Irish were very lucky to win this game (and even that against a historically-bad Michigan team), and perhaps a closer analysis would have tempered the expectations of Notre Dame fans. Without the huge disparity in turnovers and the resulting swing points, Michigan would be a hypothetical 17-14 winner of this game. Alas, turnovers are part of football, and the scoreboard ended with a big win for Notre Dame. What doesn’t make sense, however, is claiming that the Irish beat down Michigan  Wisconsin started the season as a top-10 team, and were still in the upper echelon of college football heading into this game. They brought an undefeated record into Ann Arbor expecting to emerge with a fourth victory. In the end, though, the Badgers would be dealt the first of their many losses on the season. The margins were kind to Michigan in the this game. The Wolverines were outgained by 116 yards (0.62 per play) and 4 first downs, committed more turnovers than their opponent, and even scored fewer swing points than the Badgers. However, they managed to come away with the win. How? The answer lies in points per score. The Badgers, like Utah before them, were forced to settle for field goals, while the Wolverines scored only touchdowns. In fact, the Badgers had 3 swing scores, but only gained 9 points on all of them combined. Michigan, on the other hand, had only 1 swing score, but John Thompson, of all people, made it count by taking the interception all the way back. Wisconsin had 4 field goal attempts (one was missed) and Michigan didn’t attempt a single 3-pointer. Making each score count was huge for Michigan. Wasted yards were also a big factor in this game, as Wisconsin wasted nearly as many yards as they used on scoring drives, while Michigan wasted about one third of theirs.

Wisconsin started the season as a top-10 team, and were still in the upper echelon of college football heading into this game. They brought an undefeated record into Ann Arbor expecting to emerge with a fourth victory. In the end, though, the Badgers would be dealt the first of their many losses on the season. The margins were kind to Michigan in the this game. The Wolverines were outgained by 116 yards (0.62 per play) and 4 first downs, committed more turnovers than their opponent, and even scored fewer swing points than the Badgers. However, they managed to come away with the win. How? The answer lies in points per score. The Badgers, like Utah before them, were forced to settle for field goals, while the Wolverines scored only touchdowns. In fact, the Badgers had 3 swing scores, but only gained 9 points on all of them combined. Michigan, on the other hand, had only 1 swing score, but John Thompson, of all people, made it count by taking the interception all the way back. Wisconsin had 4 field goal attempts (one was missed) and Michigan didn’t attempt a single 3-pointer. Making each score count was huge for Michigan. Wasted yards were also a big factor in this game, as Wisconsin wasted nearly as many yards as they used on scoring drives, while Michigan wasted about one third of theirs. The Illinois game was really the beginning of the end for Michigan’s season. The slide, momentarily halted by an exciting win over Wisconsin, resumed in full force at home against the Illini. The defense, expected to keep Michigan in games in 2008 until the offense came around, began a slide of its own, which would continue for the remainder of the year. Juice Williams set a Big House record with 431 yards accounted for on his own. Michigan turned the ball over twice, one of which turned into 7 Illinois points. However, Michigan did, at one point, look like a competent team in this game. The Wolverines led 17-14 at halftime after their lack of depth did them in later in the game (get used to this; it’s something of a theme in Michigan’s 2008 season). Illinois dominated the second half, outscoring Michigan 31-3. A rudimentary analysis of the margins bears that out. The Illini outgained Michigan by more than 2 yards per play, wasted 20% of their yards while Michigan wasted 43%, had more swing points, total yards, first downs, etc. Led by Juice Williams, the illini were simply the better team on this day. Of course, the Illini, like the Wolverines, would unravel later in the year. The win in Ann Arbor was almost certainly Illinois’s best performance of the year. The fact that it came against the anemic offense of Michigan is understandable.

The Illinois game was really the beginning of the end for Michigan’s season. The slide, momentarily halted by an exciting win over Wisconsin, resumed in full force at home against the Illini. The defense, expected to keep Michigan in games in 2008 until the offense came around, began a slide of its own, which would continue for the remainder of the year. Juice Williams set a Big House record with 431 yards accounted for on his own. Michigan turned the ball over twice, one of which turned into 7 Illinois points. However, Michigan did, at one point, look like a competent team in this game. The Wolverines led 17-14 at halftime after their lack of depth did them in later in the game (get used to this; it’s something of a theme in Michigan’s 2008 season). Illinois dominated the second half, outscoring Michigan 31-3. A rudimentary analysis of the margins bears that out. The Illini outgained Michigan by more than 2 yards per play, wasted 20% of their yards while Michigan wasted 43%, had more swing points, total yards, first downs, etc. Led by Juice Williams, the illini were simply the better team on this day. Of course, the Illini, like the Wolverines, would unravel later in the year. The win in Ann Arbor was almost certainly Illinois’s best performance of the year. The fact that it came against the anemic offense of Michigan is understandable. Toledo, or as Michigan fans know it “ARGJGRFGRGFGHGH.” Michigan, despite being the more talented team, managed to lose to a MAC team, and a bad one at that. How did it happen? Surely there was a ridiculous difference in the margins, no? Surprisingly, that isn’t so much the case. The Rockets outgained Michigan 327-290 (4.54-4.39 per play), and had a deficit of only 2 first downs. Michigan, in fact, seemed to get its lunch handed to it. HOWEVA, the Wolverines were actually able to hold the Rockets when they needed to: only 78 of Toledo’s yards contributed to a score of any type. The Rockets wasted the vast majority of their yardage. Michigan used a little more than a third of theirs for scores. So how did the Rockets win? Michigan’s season-long bugaboo, the turnover, resulted in this Toledo victory. The rockets had 10 swing points, including an interception return of 100 yards by Tyrell Herbert. Michigan had no swing points, and only benefitted from one Rockets turnover. If not for a missed field goal by KC Lopata at the end of the game, the Wolverines still would have had a chance to take this one in overtime. The yards-per-play, not among the worst of Michigan’s season, contributed to one of the lowest scoring outputs based on timing. Michigan turned the ball over at the worst possible instants. On Herbert’s interception return, the Wovlerines had driven the field and were going in for the score. Had that turnover not taken place, Michigan would have likely won this game – not even accounting for the momentum swing it created.

Toledo, or as Michigan fans know it “ARGJGRFGRGFGHGH.” Michigan, despite being the more talented team, managed to lose to a MAC team, and a bad one at that. How did it happen? Surely there was a ridiculous difference in the margins, no? Surprisingly, that isn’t so much the case. The Rockets outgained Michigan 327-290 (4.54-4.39 per play), and had a deficit of only 2 first downs. Michigan, in fact, seemed to get its lunch handed to it. HOWEVA, the Wolverines were actually able to hold the Rockets when they needed to: only 78 of Toledo’s yards contributed to a score of any type. The Rockets wasted the vast majority of their yardage. Michigan used a little more than a third of theirs for scores. So how did the Rockets win? Michigan’s season-long bugaboo, the turnover, resulted in this Toledo victory. The rockets had 10 swing points, including an interception return of 100 yards by Tyrell Herbert. Michigan had no swing points, and only benefitted from one Rockets turnover. If not for a missed field goal by KC Lopata at the end of the game, the Wolverines still would have had a chance to take this one in overtime. The yards-per-play, not among the worst of Michigan’s season, contributed to one of the lowest scoring outputs based on timing. Michigan turned the ball over at the worst possible instants. On Herbert’s interception return, the Wovlerines had driven the field and were going in for the score. Had that turnover not taken place, Michigan would have likely won this game – not even accounting for the momentum swing it created. On a macro, game-long level, Penn State dominated Michigan. The Wolverines had fewer yards (total and per-play), fewer first downs, worse starting field position, and 29 fewer points. However, it is important to point out Michigan’s success in the first half, after which they led 17-14 (including a Penn State drive with only 2 minutes left in the half to bring the margin back within a field goal). At the beginning of the second half, the tides turned. Steve Threet got hurt, Nick Sheridan took a safety, and it was all downhill from there. The momentum-killing 2-pointer led to a second-half shellacking at the hands of the Nittany Lions, and they followed it with 30 more points, including 10 more swing points. A greater man than I would look at the marginal analysis of each half of this game, to see the radical tale-of-two-halves. Without looking at the actual data, I would assume Michigan fairly dominated the first two quarters straight up, while Penn State controlled the third and fourth. Aided by the swing points they they scored, the second half was an ugly, ugly thing to behold for Michigan fans. Like the Illinois game, it was partially a testament to the lack of depth across the board on Michigan’s roster. Once the depth is built up, games aren’t likely to continue this familiar path.

On a macro, game-long level, Penn State dominated Michigan. The Wolverines had fewer yards (total and per-play), fewer first downs, worse starting field position, and 29 fewer points. However, it is important to point out Michigan’s success in the first half, after which they led 17-14 (including a Penn State drive with only 2 minutes left in the half to bring the margin back within a field goal). At the beginning of the second half, the tides turned. Steve Threet got hurt, Nick Sheridan took a safety, and it was all downhill from there. The momentum-killing 2-pointer led to a second-half shellacking at the hands of the Nittany Lions, and they followed it with 30 more points, including 10 more swing points. A greater man than I would look at the marginal analysis of each half of this game, to see the radical tale-of-two-halves. Without looking at the actual data, I would assume Michigan fairly dominated the first two quarters straight up, while Penn State controlled the third and fourth. Aided by the swing points they they scored, the second half was an ugly, ugly thing to behold for Michigan fans. Like the Illinois game, it was partially a testament to the lack of depth across the board on Michigan’s roster. Once the depth is built up, games aren’t likely to continue this familiar path. Sometimes, little brother wins. This was one of those instances. Sparty had more rushing yards, more passing yards, more first downs, and a significant advantage in yards-per-play. Michigan turned it over once more than did Brian Hoyer, and even though they had the game’s only swing points (on a terrible call that gave Brandon Minor a TD reception), they really had their asses handed to them. Still notable, however, is that this game was tied after three quarters. Again, Michigan’s lack of depth did them in late in the game. Looking to the future, the Wolverines really weren’t as close to Michigan State this year as they’d like to think (of course, how close can you expect a 3-9 team to be to a 9-4 team?). With Sparty losing their QB and RB, however, the Wolverines can make up ground next year.

Sometimes, little brother wins. This was one of those instances. Sparty had more rushing yards, more passing yards, more first downs, and a significant advantage in yards-per-play. Michigan turned it over once more than did Brian Hoyer, and even though they had the game’s only swing points (on a terrible call that gave Brandon Minor a TD reception), they really had their asses handed to them. Still notable, however, is that this game was tied after three quarters. Again, Michigan’s lack of depth did them in late in the game. Looking to the future, the Wolverines really weren’t as close to Michigan State this year as they’d like to think (of course, how close can you expect a 3-9 team to be to a 9-4 team?). With Sparty losing their QB and RB, however, the Wolverines can make up ground next year. Purdue had 522 yards of total offense. Of course, that does include a 61-yard fake punt and a 32-yard hook-and-ladder, but is 429 yards against one of the league’s sputtering offenses really that much of an improvement? The points scored on those two drive aren’t technically “swing points” but they are certainly unconventional ways in which Purdue ended up scoring, and in effect do the same thing. Without those two scores, Michigan would have won. Of course, the Boilermakers still would have outgained Michigan by 129 yards and 0.4 yards per play. The margins were fairly even in this game, as each team had 7 swing points (Michigan’s on a punt return for touchdown, Purdue’s on a fumble recovery that gave them the ball just 14 yards from paydirt), a single turnover, and identical starting field position. So yeah, that 3-3-5 experiment really sucked. Thanks, Tony Gibson. The Wolverines, afraid of the rushing threat by redshirt freshman quarterback Justin Siller, went with a run-oriented defense. In stopping the run (Purdue still ran for 256 yards, 77 of them by Siller), the Wolverines gave up the short passing game. Siller threw for 266 and 3 touchdowns, with no turnovers. The Boilermakers wasted 22% of their yards, while Michigan didn’t use 17%. Again, the timing of big plays by either team tell more of the story than the yardage itself.

Purdue had 522 yards of total offense. Of course, that does include a 61-yard fake punt and a 32-yard hook-and-ladder, but is 429 yards against one of the league’s sputtering offenses really that much of an improvement? The points scored on those two drive aren’t technically “swing points” but they are certainly unconventional ways in which Purdue ended up scoring, and in effect do the same thing. Without those two scores, Michigan would have won. Of course, the Boilermakers still would have outgained Michigan by 129 yards and 0.4 yards per play. The margins were fairly even in this game, as each team had 7 swing points (Michigan’s on a punt return for touchdown, Purdue’s on a fumble recovery that gave them the ball just 14 yards from paydirt), a single turnover, and identical starting field position. So yeah, that 3-3-5 experiment really sucked. Thanks, Tony Gibson. The Wolverines, afraid of the rushing threat by redshirt freshman quarterback Justin Siller, went with a run-oriented defense. In stopping the run (Purdue still ran for 256 yards, 77 of them by Siller), the Wolverines gave up the short passing game. Siller threw for 266 and 3 touchdowns, with no turnovers. The Boilermakers wasted 22% of their yards, while Michigan didn’t use 17%. Again, the timing of big plays by either team tell more of the story than the yardage itself. After being shredded by Purdue, clearly Michigan stood no chance against the potent(ish) offense and ball-hungry defense of Minnesota. Uh, not so much. The Wolverines turned the ball over once (matched by the Gophers) and gave up by far its fewest yards of the season. Michigan almost doubled up the Gophers in yard-per-play (and more than doubled their number of first downs), Nick Sheridan was competent, and Wolverines fans perhaps got a glimpse of what the future could look like under Rich Rodriguez. The gophers wasted nearly half of their yards, and Michigan wasted less than a quarter of their own. In every single way, the margins bear out that this was a dominating performance by Michigan. The Wolverines outdid the gophers in every marginal category except swing points and turnovers, in which the two teams were even.

After being shredded by Purdue, clearly Michigan stood no chance against the potent(ish) offense and ball-hungry defense of Minnesota. Uh, not so much. The Wolverines turned the ball over once (matched by the Gophers) and gave up by far its fewest yards of the season. Michigan almost doubled up the Gophers in yard-per-play (and more than doubled their number of first downs), Nick Sheridan was competent, and Wolverines fans perhaps got a glimpse of what the future could look like under Rich Rodriguez. The gophers wasted nearly half of their yards, and Michigan wasted less than a quarter of their own. In every single way, the margins bear out that this was a dominating performance by Michigan. The Wolverines outdid the gophers in every marginal category except swing points and turnovers, in which the two teams were even. rMichigan outgained Northwestern by 7 yards, but they also ended up 7 short of the Wildcats in a much more important measure – points. The Wolverines scored the game’s only swing points (on a blocked punt returned to the endzone by walkon Ricky Reyes). So with advantages in perhaps the two most important categories, on top of field position, how did Michigan lose to Northwestern? The answer lies instead in wasted yards. Michigan had great field position on their first drive (Northwestern’s 8), but Nick Sheridan tossed two incompletions and KC “Kicking Consistency” Lopata missed a field goal. The offense came away empty-handed, perhaps setting the tone for the whole game. The timing of turnovers is an important factor, that isn’t readily apparent just from looking at the boxscore or the marginal analysis. Michigan’s first turnover was a killer in terms of timing. Though the 39-yard drive that ensued from that turnover doesn’t count as “swing points” in the strict terms of being shorter than 25 yards, it wasn’t far off. The missed opportunity for Michigan combined with the opportunity given directly to Northwestern. certainly hurt Michigan on the final scoreboard. This was a game that Michigan could have won, based on marginal analysis.

rMichigan outgained Northwestern by 7 yards, but they also ended up 7 short of the Wildcats in a much more important measure – points. The Wolverines scored the game’s only swing points (on a blocked punt returned to the endzone by walkon Ricky Reyes). So with advantages in perhaps the two most important categories, on top of field position, how did Michigan lose to Northwestern? The answer lies instead in wasted yards. Michigan had great field position on their first drive (Northwestern’s 8), but Nick Sheridan tossed two incompletions and KC “Kicking Consistency” Lopata missed a field goal. The offense came away empty-handed, perhaps setting the tone for the whole game. The timing of turnovers is an important factor, that isn’t readily apparent just from looking at the boxscore or the marginal analysis. Michigan’s first turnover was a killer in terms of timing. Though the 39-yard drive that ensued from that turnover doesn’t count as “swing points” in the strict terms of being shorter than 25 yards, it wasn’t far off. The missed opportunity for Michigan combined with the opportunity given directly to Northwestern. certainly hurt Michigan on the final scoreboard. This was a game that Michigan could have won, based on marginal analysis. Again Michigan was within striking distance at halftime, and again their opponent used far-superior depth to slam the door on the Wolverines. This game, still, was closer than it seemed. Michigan missed a field goal, and turned it over twice to Ohio State’s once (14 swing points for OSU, 0 for Michigan). Sure, playing hypotheticals accomplishes almost nothing, but even without the changes in momentum that those events produced, that still would have meant only a 28-10 loss for Michigan, far from a blowout. But as we learned in the Notre Dame game, turnover and swing points do indeed count on the final scoreboard, and Michigan was demoralized by the Buckeyes for the second year in a row.

Again Michigan was within striking distance at halftime, and again their opponent used far-superior depth to slam the door on the Wolverines. This game, still, was closer than it seemed. Michigan missed a field goal, and turned it over twice to Ohio State’s once (14 swing points for OSU, 0 for Michigan). Sure, playing hypotheticals accomplishes almost nothing, but even without the changes in momentum that those events produced, that still would have meant only a 28-10 loss for Michigan, far from a blowout. But as we learned in the Notre Dame game, turnover and swing points do indeed count on the final scoreboard, and Michigan was demoralized by the Buckeyes for the second year in a row.